The Design World’s Color Guru

Courtesy of India Mahdavi. Photography by Antoine Doyen.

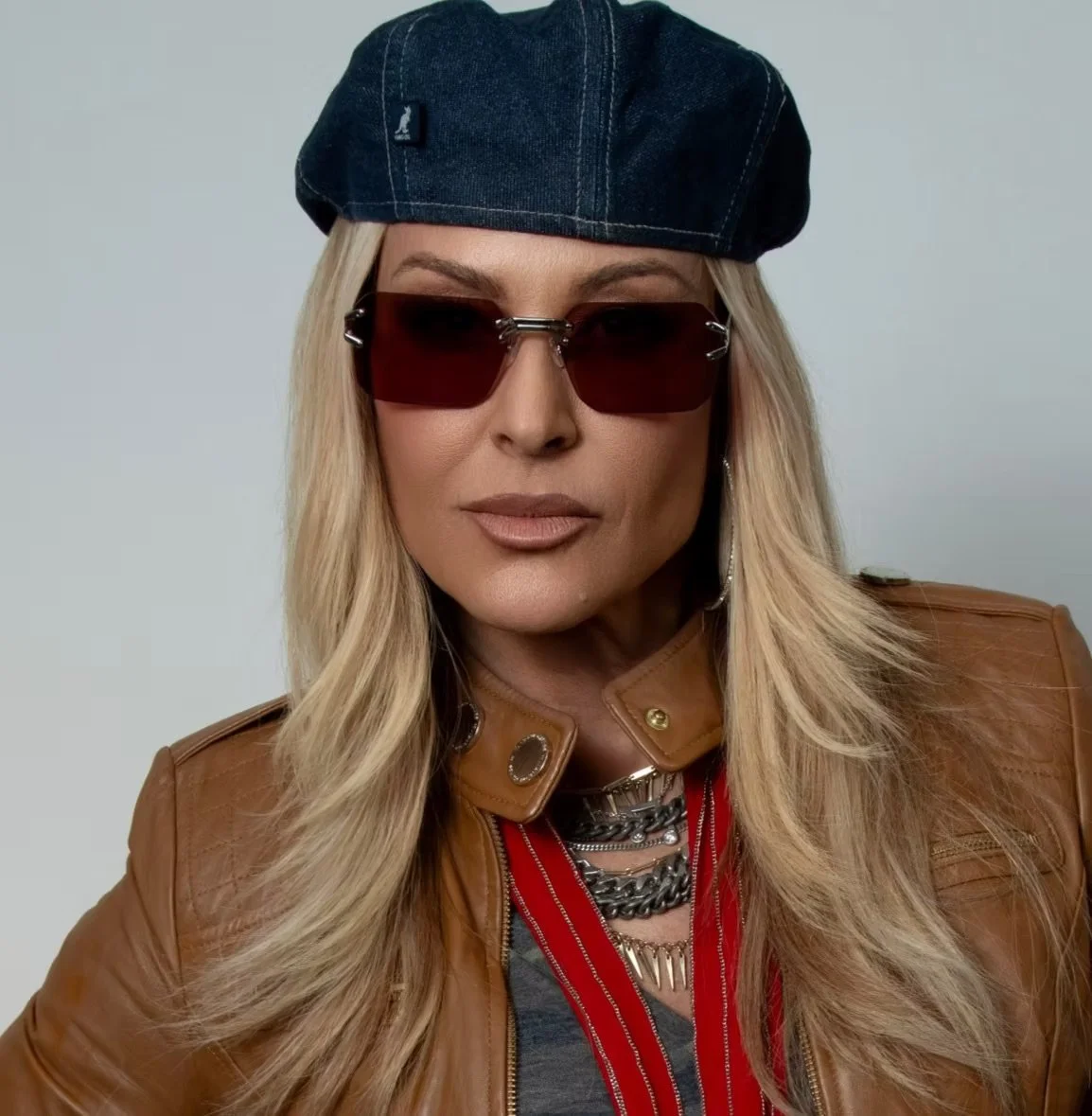

India Mahdavi

The Design World’s Color Guru

By Bonnie Langedijk

In culture, there are only a handful of people who shape it—India Mahdavi is one of them. With her distinct style, the Iranian-French designer and architect has brought joy and humor back to design. Known as the queen of color, Mahdavi’s work explores the intersection of craft, design and psychology while continuously pushing the boundaries on what makes a space a good one. Over the years, Mahdavi has crafted memorable identities for iconic spaces including the pink Gallery at Sketch London, Ladurée in Los Angeles and Tokyo and Hotel du Cloitre in Arles. Her collaborations—long before it became a trend—include partnerships with luxury brands like Dior and furniture makers like Gebrüder Thonet Vienna, always maintaining her signature Pop-inspired lens.

But her extensive body of work—spanning everything from furniture and objects to large-scale interiors—goes far beyond aesthetics. Mahdavi’s designs are about connection—creating spaces that evoke emotion and invite people to engage with their surroundings and each other. With over two decades of work, Mahdavi’s vision remains clear; design should make you feel something.

India Mahdavi’s Project Room on Rue Las Cases. Photography by Tom Dagnas, courtesy of India Mahdavi.

India Mahdavi’s Project Room on Rue Las Cases. Photography by Thierry Depagne, courtesy of India Mahdavi.

Bonnie: I’ve heard there’s an India Mahdavi street in Paris. I’m intrigued, tell me more.

India: I settled in rue las Cases over 20 years ago. I have my studio, my own furniture showroom and the “petits objets” which operates like a shop, all on the same street. I opened The Project Room in 2020, which is a space of free expression, where we do exhibitions, invite curators and other galleries to show or host pop-ups. Recently, I have reprogrammed a little space connected to my showroom that I call The Tiny Room. It will be a space for young designers to show their work like I recently did for Wendy Andreu during Paris Design Week. I think it's a very singular model and it creates a nice little ecosystem. I had no preconceived idea as to how I would deploy my activities as an interior designer [within these spaces]. The organic expansion was merely driven by intuition as if the spaces themselves called and guided my actions. I liked the idea of a horizontal expansion on one single street, where one activity could feed another creatively and economically creating a rhizomatic ecosystem. It's a very local organization and has gained global recognition over the years.

I haven't heard of anyone doing that before. I can imagine it creates a deeper dialogue between disciplines, and also between generations.

India: It's an ecosystem that works because it's on one street. When you put something in the showroom, you see how people respond to it. It's great to have that connection.

“I liked the idea of a horizontal EXPANSION on one single street , where one activity could feed another creatively and economically creating a rhizomatic ecosystem..”

When you're open to inviting other people into your narrative, you have to take your own ego out of the equation. Not everyone has that confidence.

India: When I started I had to create my own name. Now, I think there's such beauty in collaborations, in bringing people in and sharing. It's a very different era, I think.

I hope so. I find it interesting to speak with designers and people who work in creative fields to talk about this concept of taste. How do you relate to the concept and what are some of the key elements that helped develop your own?

India: I think of taste as a form of harmony. Sometimes having disharmony is as interesting as having harmony. Too much taste kills the taste, too much harmony is boring. To be tasteful is a concept that's slightly bourgeois for me. I find beauty and taste in things that are supposedly distasteful because there's a reality and an authenticity to it. I can relate to many different people's tastes because what I'm interested in is seeing a personal vision of something that enters other people's worlds. I try to work on harmonies and it's like a musicality more than anything else. The way I work with colors, is the way a poet would work with words. It's a rhythm, a vibration.

Taste as a concept also becomes increasingly difficult because I think people are becoming more and more afraid to express their taste. We see so much, that it almost creates this idea as if there's good and bad taste.

India: I don't think about whether this is good taste or bad taste, this is beautiful or not beautiful. I'm more concerned about the meaning of things. I'm more concerned with the vibration and the light, which can bring a sense of joy. I'm against restrictions. In schools, they teach you to have a certain taste. I've traveled the world. In Iran and Egypt, for example, I have seen unexpected encounters of different styles that are fabulous. Is it good taste? No, but it makes it surrealistic. The way I work is also a result of my background and my travels. The memories and the emotions I constantly convene in my work

Do you think your nomadic childhood has impacted your sense of space or how you adapt yourself to the world around you?

India: I think my sense of space came from my studies of architecture. I remember the excitement I would feel when I discovered beautiful spaces as a young girl. I was in awe when I first visited Fondation Maeght. Having that excitement and those emotions, is what I'm trying to recreate for others. My travels have influenced my relation to color. I grew up in Cambridge, Massachusetts. My first memories are technicolor. It was the mid 60s and everything was so colorful. Then I moved from Cambridge, Massachusetts to Heidelberg, Germany and it went from technicolor to black and white. Suddenly you miss the joy. It's a whole new landscape of colors and materials. When I moved to the South of France, the light and the color resurfaced into my life. During my seven years of studying architecture, I learned how to structure spaces. My work isn’t only about ornaments or color. The spaces we design are quite structured, with attention to flow and circulation. Today, I work mostly with existing buildings. I create concepts or three-dimensional identities for public and residential spaces. My relation to space is also very much coded by sort of a rhythm. It's not only the decorative part, it's also the rhythm of the spaces. Every space can surprise you. The way you cut out space is a bit like a book.

Villa Medici. Photography by Francois Halard, courtesy of India Mahdavi.

It's alive, right?

India: When you work on spaces, you're also working on a narrative. A bit like a scenario. You enter a space, and you have to consider what happens next What emotions you spark, and what experience you can offer.

Your work very often is referred to as joyful. I think that's also aligned with the use of color. It has a sense of humor or sort of wit. What's your relationship to humor, and how do you bring that into your work?

India: I want to enter with a smile on my face. I‘m also out fighting against my melancholia. I'm always trying to find a balance between the meaning and the fun, while always aiming to trigger an emotion.

I loved the project you did with Villa Medici in Rome and the contrast you created between the new and old, traditional and contemporary. What was it like to work within such an iconic environment, and is that contrast between modern and contemporary and traditional and heritage something you think about in your work?

India: It was quite intimidating because the villa is such a cultural institution. From the moment we started discussing the project, it was clear that the building’s character was untouchable: floors, walls, and ceilings were not subject to renovation. Therefore, our intervention was more about furnishing than interior architecture. It was about orchestrating complex narratives, allowing the imagination to wander, creating a dialogue between different styles of furniture, and developing a graphic work reflected in the elements of the project. It’s the kind of project that requires humility and boldness at the same time. It wasn’t easy to find the right balance. How do you add to the beauty of these spaces without taking away from it? These rooms are very spacious, about 70m2, 5 meters high, wall patinas by Balthus, renaissance friezes by Jacopo Zucchi, and only one window with a very high windowsill, overlooking the most incredible view of Rome. The richness of these references inspired us to design furniture specifically for these spaces. Like Balthus and Peduzzi, we drew from Renaissance masters—Piero della Francesca, Fra Angelico, and Filippo Lippi. For the Galilei and Debussy rooms, we designed bed architectures in the tradition of the studiolo, as resting thrones from which visitors could enjoy an exceptional view of the city. It's like the Pop version of Renaissance, using all the craft of French marquetry—which is also part of Italian history—and integrating all the savoir-faire into the process.

That’s incredible.

India: When Sam Stourdzé [the director of Villa Medici] invited me to participate in the ‘re-enchanting the Villa Medicis’ program, by entrusting me with the Piano Nobile, there were two goals. One was to work with the collection of Mobilier national, and two; to include the craft of the talented French and Italian makers. with all the French or Italian craftspeople. It's a governmental project so there's very little budget. The composition was subtle: it involved replacing furniture that seemed out of place while keeping those that fit into the story we wanted to tell. We focused on French and Italian furniture from the 17th to the 20th centuries—pieces inherited from the French Academy in Rome at the Palazzo Mancini, acquisitions made by Balthus, and creations by Richard Peduzzi.

That's amazing.

India: But maybe that wasn't your question. What was your question?

The Gallery at The Sketch, designed by India Mahdavi. Photography by Thomas Humery, courtesy of India Mahdavi.

The Gallery at The Sketch, designed by India Mahdavi. Photography by Dave Benett, courtesy of India Mahdavi.

It was and it wasn’t. What you did so well, for me, from an aesthetic point of view is finding that contrast between the traditional and modern, contemporary and heritage. I wonder if that's something you in general think about in your work.

India: That's a good question because I think I work on the idea of familiarity. I have noticed that when you meet someone who reminds you of someone you like, there’s immediate sympathy. Similarly, I work on the idea of collective memory giving a different twist or introducing more color, to create a friendly environment. The pieces we create can work in very different environments because they combine the past and the present. That's interesting.

That's interesting. I think since COVID-19 kind people have so much more awareness of furniture and design and what their home looks like because that has become such a bigger part of the narrative. But people also see designs in different contexts. How do you think social media has affected the way we interact with the spaces and the objects around us?

India: Since Covid, we’ve witnessed an explosion of imagery on social media, but we're also much more aware of what we don't see in a product, meaning where it’s made, who made it and who is selling it. People are more attracted to having a product that's very well crafted, that's made locally and is sustainable. It's not only the image that counts, it's what's behind an image. There's a new awareness of invisibility. With this incredible flow of images on Instagram, there's also this urge to create a strong image and it has led to a lot of products that are an exaggeration, nearly caricatural.

It's also how something lives in the real world versus how something lives in an image that I very much see with fashion too.

India: It has become nearly cultural. You see it in fashion, you see it in politics, you see it in many different fields. It's as if the world has become binary. You're either against it or you're for it. When you think of it, the digital world is binary, there's less space for the hues.

Spaces or even creative disciplines, whether that's fashion, design or art, can be such a great vehicle for connection. It's interesting to think about how we can design them in a way that they connect rather than disconnect in a way.

India: That's the whole point. The digital world is going to become more and more perfect with AI. What's going to become more important is your connection to reality. The experience will become more important than the image. The craft and its imperfections are going to be more important than perfection. What people like me are trying to do, and what you're trying to do, is to create human-centric spaces where people can connect, when people can share, where people can feel good and create conversations.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.