Putting Black Art at the Center

Courtesy of Faridah Folawiyo

FARIDAH FOLAWIYO

Putting Black Art at the Center

By Mazzi Odu

What is a curator with no fixed location? Is it best for an artist to not seek out gallery representation? What happens when a group of creatives of a particular race are not expected to pander to the fleeting whimsy of a global art market that might deem them valuable one minute and irrelevant the next? For Faridah Folawiyo these are not hypothetical questions but at the root of FF Projects, the nomadic curatorial concept she founded to create holistic yet radical responses to the lived experiences of black artists.

Folawiyo is far from a novice. The Nigerian artistic multi-hyphenate has been working in the contemporary art space for close to a decade and has two forthcoming shows opening in London: Manifold, a group show featuring work by 15 black female artists and I am my sister, I am myself, a solo exhibition by Fadekemi Ogunsanya and an as yet untitled project that will open in Lagos in 2023. At the center of her practice is dismantling barriers and expanding participation and appreciation of black art on every level regardless of locale. We spoke with her about how she’s achieving this, one dynamic intervention at a time.

Mazzi: You founded FF Projects as a means of disrupting the existing contemporary art model, what brought you to that decision?

Faridah: People have always told me “You need to open up a gallery.” I’ve never wanted to do it as I’ve never been so interested in the very obviously commercial side of art. But I love to travel and I love the idea of cultural relativism. When I was thinking about art, especially my relationship to black art across the diaspora I began thinking: ‘What are the ways I can create an exchange between black art and the world?’ So, my curatorial practice evolved into a series of questions. I’m not answering any questions, I’m asking a lot of questions centered around how context affects the way we exhibit and view art.

“If an artist is SUCCESSFUL in Africa the global art market can still say: “She’s not successful until she’s part of this global market.” There’s a clear disconnect there for me.”

You’ve touched upon cultural relativism and creating an exchange between black art and the rest of the world, but also not falling victim to the trappings of commercialization or being influenced by trends. How do you navigate this?

Faridah: I was reading recently that the global art market is reflective of global hierarchies anyway. So even when they incorporate African art into the global art market it is within pre-existing rules and systems based on western and Euro-centric models. Therefore, if an artist is successful in Africa the global art market can still say: “She’s not successful until she’s part of this global market.” There’s a clear disconnect there for me. As a black curator there is a duty of care. I’m invested in the work in a way that maybe white European or American gallerists are not. I can look at some artworks and realize that I don’t think this artwork would be comfortable in certain contexts. I feel that responsibility very strongly because I am cognizant of what gaze does to certain artworks. Whilst I can’t fault anyone for capitalizing on this moment as a black person, I’m worried about the long-term ramifications especially for artists. If you are having a boom right now and in five years aren't popular, what happens? It’s the responsibility of big players in this industry like the galleries, the gallerists, the auction houses to try and protect the artists and I don’t know how much that’s happening right now. With the artists I work with, I give them space and honest advice, especially because I work with young artists. I can say: “I’m young too but I have been in the art world since I was 18. It’s about focusing on your practice and feeling good about the people who connect to your work and not trying to be on any bandwagon and being part of any boons that you don’t feel are sustainable.” But that might be really bad advice. Some people might want to make a lot of money right now, but I don’t know how to change the overall system’s bar with my own interventions.

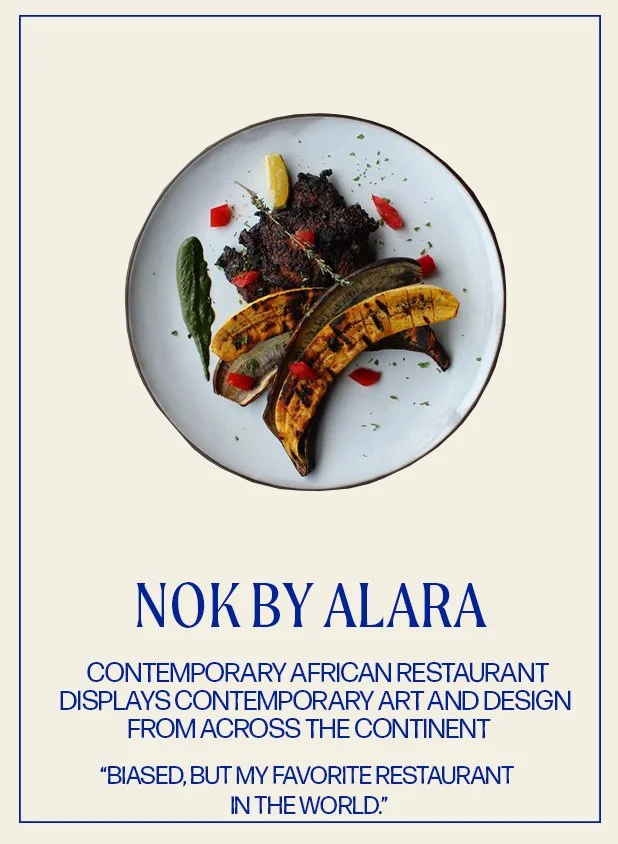

Faridah with her mother Reni Folawiyo, owner of Nok by Alara.

Let’s talk about some of those interventions, in particular your two forthcoming shows in London, I am my sister, I am myself by Fadekemi Ogunsanya and the group show Manifold; What was the genesis for both projects and what can we look forward to experiencing?

Faridah: Fadekemi and I have an interesting relationship. We first started working together when she wasn’t thinking about being an artist. She was still in architecture school, and I was brought on at the very last minute in 2018 to curate the art elements of ArtXLive! in Lagos. I always knew she had a very strong visual sense, so I just reached out to her and said: “Okay what can you do?” It turns out that she can do everything. So, we started working together. It turned out that the way we think about exhibitions is similar. For her first solo show in Lagos it became this thing where it had to be holistic and fun because we are not one-dimensional people. We made this great publication to go alongside the show. We had merch, and she showed animations alongside her paintings, her frames and her furniture. The reason why we chose London this time round was because she’s been working and creating in London for the last two years and it felt right to show the work where she’s making it. With Manifold, I was doing a lot of Diaspora postcolonial research. A lot of thinkers like Stuart Hall noted that temporalities tend to merge, so the past, the present and the future all kind of exist in one. I thought about this idea of layers: whether literally on a canvas, or a reflection of the artist's own many layers of 'selfhood' and artistic practice. Or even the fact that a lot of the artists I'm working with do more than one thing and apply themselves in lots of different ways. The exhibition is about abundance. I was thinking about it thematically and then the artists came after. I started thinking about artists where I could feel that sense of multiplicity. I wanted the artists to feel supported by each other and to have a sense of camaraderie. First and foremost because it’s important to build those communities anyway. Being a black female emerging artist is extremely difficult. I was thinking how do I make this easier for them? Perhaps they don’t have to worry too much about selling or just focus on the practice and what they feel like doing in that given moment? And that is what I said to them in my outreach email: this is a site for experimentation, and I can provide that framework. I’m not adding you for a little bit of spice. You can do what you want with the space. It’s yours.

You clearly value the importance of occupying space on one's own terms and not allowing unconscious bias or assumptions to pre-determine your personal journey or your professional goals. You have also utilized the tools and codes of understanding that your educational background affords you to widen participation in different spaces. On a personal and wider level, how do you reconcile being both establishment and to some extent anti-establishment? Do you see yourself as a pioneer given that you're young, black, female, Princeton University and Courtauld Institute educated and committed to fighting for a greater mandate for those who have been historically and systemically othered?

Faridah: I don’t think of myself as a pioneer. In a way I’m doing what white male or female curators have always done which is centering themselves. I’m centering the black woman because that’s who I’ve felt most supported by and that's who I want to support. It starts with the black woman and then moves to the black person in general, but I want to focus on black art and give it space. With my educational background I could have gone and worked for an institution, but I don’t feel it necessary to follow that very traditional route to have an impact. One of my main facets is this idea of comfort. How do we make art experiences that don’t feel intimidating? That people feel comfortable in the exhibition space. Institutions can feel very daunting and intimidating for people who didn’t grow up going to these places. Sometimes there’s some over intellectualization of these things too. Because I have that intellectual background, I use it to distill it in a way that most people can understand. I don’t believe people should be looking at art and be confused. That’s not interesting to me.

I’ve had to unlearn a lot of things because I have had that background. When I’m writing exhibition tags, I want it to read like the ones I’ve always seen. But then I pause and think how do I actually unpack this? Why am I writing like this? Who am I writing this for? Who is my audience? And rethinking the audience especially when I have had this specific educational background is very interesting to me. It’s something I’m constantly working on. I still write but I struggle with how I describe my writing. I’m an art historian but not a critic. I’m a super intuitive person so when I feel good about something I do it.

The flyer for Faridah’s upcoming show opening in London. Manifold is a group show featuring work by 15 black female artists.

Courtesy of Faridah Folawiyo

Your career has been one that has had quite a few risks: from working in different locations to further expanding your own artistic practice, what do you think motivates you to keep pushing boundaries?

Faridah: In many ways my route has also been unconventional. When I first moved back to Lagos, I actually moved back to open Nok Restaurant so I was working in the family business. I think the level of confidence shown in me at a young age made it easy for me to believe in myself and set up on my own. I recently co-founded No Fronting in London. We are a collective of four female artists creating spaces where you can consume art and listen to music. We explore what it means to commune essentially. The kind of almost spiritual feeling of communing especially as black women. It’s somewhere you can just be, on your own terms in a safe space.

You’ve had such a rich and varied career so far and one that belies your age: do you have a clear vision of what success looks like to you long term?

Faridah: For me, success is about the artists feeling successful. I basically want the artists to get the recognition they deserve. I also continually ask myself ‘Am I creating a framework for artists and audiences to feel that they can be supported in some way, shape or form? Am I creating experiences they want to see? Am I creating a little break in their day where they can have a moment for themselves and feel something? If I can have that kind of impact, then I think success is essentially that. Ultimately, I will stop moving around and I think when I’m more static, I will be in Nigeria. The end vision will be with something that is not a museum and is not a gallery. But for now I’m enjoying experimenting until I get to a point where I know what it looks like.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.