Charlotte Perriand Through her Daughter’s Eyes

Charlotte Perriand en Savoie face à la montagne, 1930 ©Archives Charlotte Perriand, ADAGP 2024

Pernette Perriand-Barsac

Charlotte Perriand Through her Daughter’s Eyes

By Bonnie Langedijk

Charlotte Perriand didn’t just design furniture—she designed ways of living. A pioneer of modernity, she approached each space, object, and collaboration as a conversation between human need, natural beauty, and technological possibility. She believed in creating for the many, not the elite, infusing her designs with a distinctly personal, sensual touch. Her creations, spanning nearly a century, were never about fleeting trends. They were about purpose. But for Perriand, purpose had nothing to do with simplicity for its own sake. She rejected the label of “designer,” preferring to call herself an architect—of objects, interiors, and ideas. She believed in design as a means of togetherness, as an art of living (“l’art de vivre”) that aligned people with their surroundings and each other.

Today, Perriand’s legacy isn’t just preserved; it thrives. At its heart is Pernette Perriand-Barsac, Perriand’s daughter and one of the most devoted custodians of her mother’s vision. Growing up amid a whirlwind of sketches, prototypes, and collaborators like Le Corbusier and Jean Prouvé, Pernette witnessed her mother’s pragmatic creativity. Perriand-Barsac worked alongside her mother for over two decades, immersed in her philosophy that prized human-centered design above all.

In the years since Charlotte Perriand’s passing, Perriand-Barsac has become the guardian of her mother’s legacy alongside her husband, historian Jacques Barsac. The duo doesn’t just preserve her designs but the stories, principles, and radical optimism behind them. Together with Cassina, Perriand-Barsac breathes new life into her mother’s work, ensuring its relevance in a world grappling with questions Perriand anticipated decades ago: How do we live better? How do we design for the many, not the elite?

This year, Cassina reissues a curated selection of never mass-produced models and previously unseen versions of icons already in catalogue to celebrate the 20th anniversary of the Charlotte Perriand Collection, reaffirming her status as a pioneer of modern design. Among the highlights are a 30-piece limited edition of the Ventaglio table, Vase à fleurs échancré–a design never produced before, and the Indochine chaise longue crafted from innovative materials.

But we’ll let Pernette do the talking.

Charlotte Perraind et Pernette Perriand, Rio, 1987 ©Archives Charlotte Perriand, ADAGP 2024 .

Montparnasse Atelier © Archives Charlotte Perriand ADAGP2024

Do you remember the first time you were made aware of the concept of design?

My mother hated the notion of design. Although she was one of the great precursors of design, she used to say: "I am not a designer, I am an architect." Creating an object for the sake of an object did not interest her. It had to be part of a whole, of an architecture, of togetherness. It was the "whole" that excited her imagination to create an object.

“In our APPROACH to collecting design, we look for pieces that are not only artistically significant but also reflective of their cultural and historical context.”

Your mother was a highly celebrated woman in the world of design, and still is. Has it ever been strange for you to see her as both your mother and this design legend?

It was natural for me. Her profession and her life were deeply connected. As a child, I knew my mother's friends: Fernand Léger, Le Corbusier, Pierre Jeanneret, Jean Prouvé etc. It was like all parents’ friends. When I went to Fernand Léger's house, I exchanged drawings with him. I went to the circus with him. He loved children.

Did they ever feel as separate people to you?

Yes. Because she was rarely available. She worked all the time and traveled a lot.

Charlotte Perriand had a unique understanding of “art de vivre” — could you share a story or memory that captures her philosophy in the spaces she created or inhabited?

One of the best examples is “La Maison au bord de l’eau” that we did with Louis Vuitton in 2013 for Miami. In 1934 Charlotte Perriand didn’t have the opportunity to create this project. When the public entered this small 90 m2 house, terrace included, they didn’t want to leave. It was extraordinary. I remember the reaction of Pharrell Williams and his wife. They were as touched as we were.

How would you describe your mother’s approach to design?

It’s a pragmatic approach. “There is no formula," she said. She worked with crafts or factories. Everything depended on the place and the programme and she did not exclude any materials: metal; wood; bamboo; rubber etc. Her goal was to create for the greatest number of people and not for an elite. She adapted to the needs of the people, to the programme, to the place, to the country, to the crafts with which she worked. She took into account gestures, steps, body movements in space, the size of men, women. "Gestures, forms, technique, economy," she said. She detested decoration from when she left school in 1925 and the post-modernism of the 1980s. She was a functionalist who took into account human scale and did not exclude poetry. Her forms were sensual. She said: "Wood can be caressed. Soft as a woman's thighs".

Pernette Perriand-Barsac with the Cassina Indochine chaise longue, captured by Lea Anouchinsky.

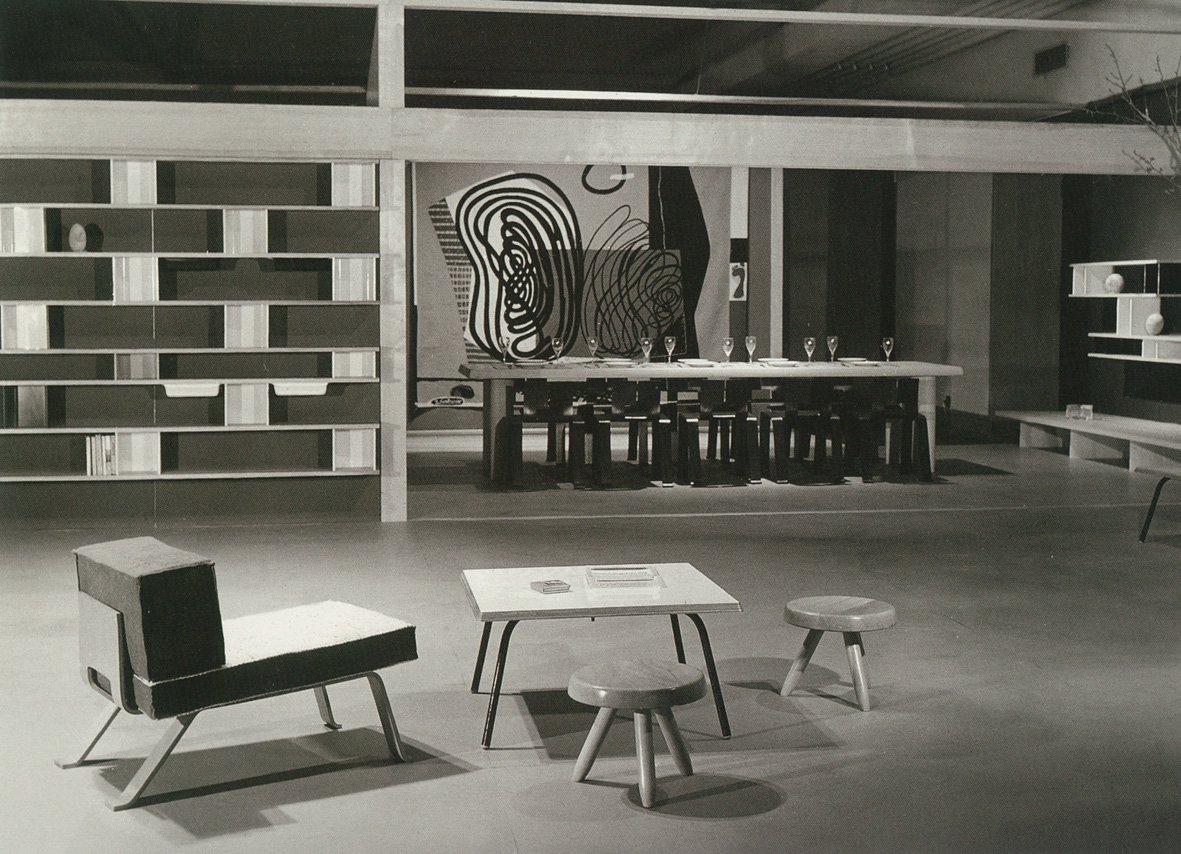

Expo Synthèse des Arts Tokyo in 1955 © Archives Charlotte Perriand ADAGP 2025.

What would you say were the leading principles in your mother’s design process?

Here is what my mother said in an interview in 1984.¹

"The driving force behind creation is need. I can only design a chair if I want to sit on one. There is part of a dream in creation. You have to take pleasure in creating something good.

“[To design and make a piece of furniture] you must take into account time, place and the means. There is a philosophy of things in life that makes you create in one way or another, considering the place. When you make interior equipment, needs, the gestures can be problematic; these gestures are in the place. Once you have located these places and studied the needs, you just have to implement them. […]

“I sit down at the drawing board only after I have thought about the gestures and the construction of a space And then you have to try the object yourself. You make a piece of furniture for yourself first. […]

“When I have dreamed up a shape from a material, I need to know which factory I am going to work with, because each factory has its own technique, its own production method. When I am in the factory, I don’t know what direction I will work in. My form will remain the same because it meets a need, because it serves me. But its framework will be expressed differently.

¹ Dominique Boudet, Michel Bourdeau. Charlotte Perriand, Un art de vivre, AMC, décembre 1984, pp. 96, 97, 98.

What was her process like?

It was a long maturation. She had to exchange thoughts with someone, me or a close friend, an engineer, a craftsman, to refine and clarify her ideas. She often did research. Developed specifications when they did not exist. She wrote everything down and looked her ideas up again a week, a month, three or ten years later. It was very organized.

Could you tell us more about your work at the Charlotte Perriand Archive?

It is thanks to the royalties that Cassina pays me that I can safeguard the archives, develop books, exhibitions, conferences, to make her work known. There are thousands of photos, plans, drawings, letters, etc. If Jacques Barsac has made my mother's complete works in 4 520 page-volumes with such quality, it’s because he works with the archives that allow us to trace 70 years of her creations!

In collaboration with Cassina, you’ve helped breathe new life into her designs. Which piece has felt most personal to revisit, and why?

My favourite piece is the Ombra Tokyo Chair in plywood from 1954. Not because I was in Japan with Charlotte in 1954, but because I believe that it’s a design masterpiece. Unfortunately, it wasn’t commercially successful. It’s sad because it’s sublime. It must be recognized that it’s quite atypical. It’s too different from other chairs to please. The public is very conservative. If a table doesn’t look like something they know, they’re afraid of it.

How does it feel to witness the evolution of your mother’s work through Cassina's re-edits and new releases?

It's a great pleasure to see these reissues. These are pieces of furniture that are 50, 60 or 70 years old, or even more, immersed into the contemporary world, together with today's designers.

Each year, with Jacques Barsac, we choose three or four of Charlotte's furniture designs that we propose to Cassina. Cassina chooses two designs in the function of its collection. And we revive these pieces that were sleeping in books or in a drawer in the archives. Cassina makes sets by mixing furniture by contemporary designers and furniture by iMaestri like Charlotte Perriand. It's very impressive to see that a table created 80 years ago dialogues so well with a chair by a current designer. The oldest is not always the one you expect.

It’s both a continuation of her vision and a new chapter because we are often obliged to slightly adapt the models to current standards. Sometimes we change the materials to dialogue with sets. This is what Charlotte often did.

Charlotte Perriand at the Expo Synthèse des Arts Tokyo in 1955 © Archives Charlotte Perriand ADAGP 2025.

The Cassina Ombra Tokyo chair, designed by Charlotte Perriand in 1954. Captured by Valentina Sommariva.

Charlotte’s work continues to evolve through this collection, yet it remains timeless. What do you believe is the secret to her designs’ enduring relevance in today’s world?

It was the hatred of decoration that led her to be so accurate in her approach: functional, plastic, technical, economical. She never sought to please or seduce at the time. She did what seemed right to her in a given situation, without forgetting the lessons of nature. She chose her clients and did not want to have a large agency. She worked with a single designer so that she was free to make choices.

Where do you see her influence most strongly, both in design and in everyday life?

It’s in design and in her relationship to the body and nature. Her approach is very contemporary. Her own life was also a precursor to today's life. She was a free woman in her body and in her mind. She divorced in 1932 at the age of 29. She was a great sportswoman. She went mountaineering, skiing, canoeing, caving, etc. I think that, from this point of view, the modern revolution is a revolution of the body. She traveled a lot. She was enriched by the cultural differences she encountered, Japan, Brazil, Europe.

How do you view the current design world?

It doesn't really invent much anymore. Everything looks a bit the same. When design is in crisis, we see the return of decoration. It's a recurring phenomenon. Paradoxically, there have never been so many new techniques, but we don't see them emerging in furniture design very much.

What shifts over the past ten years have impacted the way our spaces look and are designed?

The love of light, sun, space, materials like wood; the open kitchens that my mother advocated in 1928, just as she advocated landscape views to create continuity from the inside out.

As we live in such a visual world, many designers design with the camera in mind rather than functionality. How do you look at this visual-first world, and how do you think it impacts the quality of design?

In the long term, this could be catastrophic. Design is not an image. We do not live in 2D. Design is first and foremost an approach in space for human beings who have functional and emotional needs. Design also responds to the body’s needs in time and economy.

There’s a whole new generation of people who are only just beginning to become familiar with Charlotte Perriand and her work. What do you hope these people will remember about your mother’s legacy?

That you have to remain "fan-eyed" throughout your life, that is to say curious, attentive to others, to nature, to poetry, to living together. She writes in her autobiography²: "Man and the universe are intimately connected, which is why I can never separate the parts of the whole in my discipline, the architecture of the environment, the furniture equipment of architecture."

² Charlotte Perriand, Une vide de création, page 24.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.