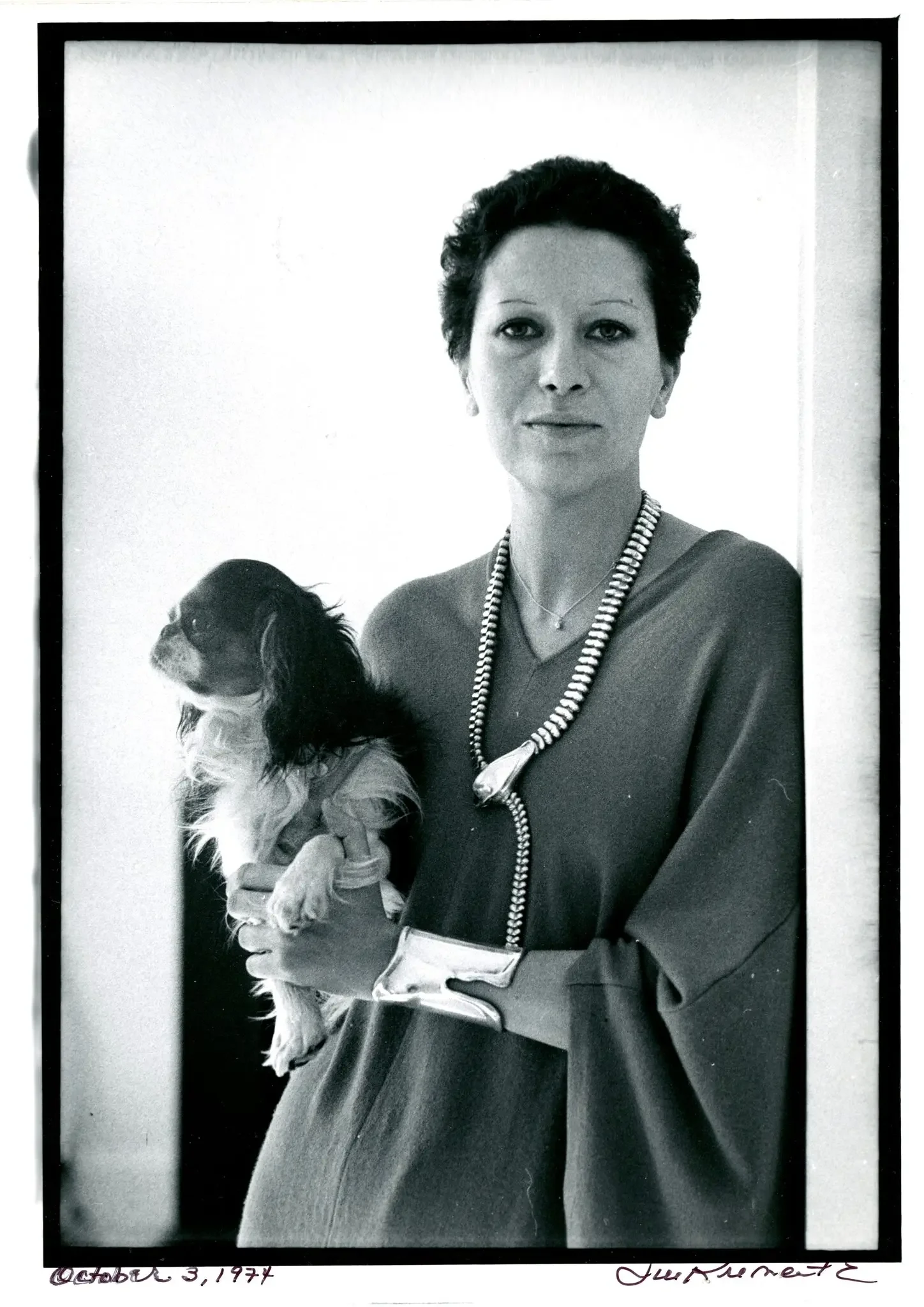

Sarita Posada

Courtesy of Sarita Posada, photography by Jen Steele.

HURS CURATORS

SARITA POSADA

The interior designer on her go-to tools and Elsa Peretti

The best interiors don't look designed—they look inevitable. Sarita Posada understands this better than most. Colombian-born, Portland-raised, New York-based, she learned her craft at André Balazs's hotels alongside Shawn Hausman before launching a studio that now works across retail, hospitality, and residential with equal fluency. Her clients, including Aimé Leon Dore, A24 and Palm Heights, come to her for a particular skill: the ability to extend their world into physical space while leaving her own fingerprints all over it. Her approach borrows from historical design without tipping into pastiche; there's an instinct for knowing when to hold back. The result is rooms that feel specific and timeless, refined but never precious.

A 1970s JEWELRY BOX, SIGNED PERETTII

Elsa Peretti arrived at Tiffany & Co. in 1974, and the house—which hadn't touched silver jewelry since the Depression—was never quite the same. She insisted on the material when it was considered decidedly unglamorous; she was right, of course. Her organic, sensual forms became signatures of a new American elegance, pieces women could buy for themselves, wear to sleep, forget about entirely. Half a century later, her designs remain as covetable as ever—proof that true style doesn't date, it simply waits for the rest of us to catch up. The Wave Jewelry Box, designed in the 1970s, is Peretti at her most tactile: molded leather, hand-applied oxblood finish, Italian-made. Seven inches wide, curves for days. But we'll let Sarita do the talking.

“This was an anniversary gift so it’s particularly SPECIAL to me. The color is the perfect shade of oxblood and the combination of the different leather textures is so tactile and makes the simple act of putting away jewelry a pleasant ritual.”

“I was born in Medellín and most of my family is still there, so this is always one of my first stops when I'm home. The museum, founded almost 50 years ago, is a reminder to me of Colombian RESILIENCE . It survived the difficult socio-political conditions of Medellin in the 80s and 90s and now houses an extensive collection of Colombian modern art which is always a pleasure to visit and reconnect with.”

IN MEDELLIN, NINE ARTISTS STARTED A MUSEUM WITH NOTHING

When the Medellín Museum of Modern Art was founded in 1978, it had no building and no collection—just a group of young local artists who thought their city deserved a forum for contemporary work. By 1980, MAMM had found a home in the Carlos E. Restrepo neighbourhood. The collection now numbers over 2,400 works, predominantly Colombian artists from 1950 onwards, with Débora Arango—Medellín's own enfant terrible, ostracised for decades for her unflinching takes on women's rights, political corruption, and Catholic hypocrisy—as its beating heart. In 2009, the museum moved into a former steel foundry in Ciudad del Río. The transformation feels apt: the city rebuilt itself, and so did MAMM.

IN PARIS, AN ITALIAN RESTAURANT WITH NEW YORK HOURS

Tucked into the Rive Gauche on rue du Sabot, Cherry delivers Italian-American with the easy cool of a Brooklyn jazz bar and the polish of Saint-Germain-des-Prés. Sarita Posada Interiors designed the interiors: walnut panelling, red velvet banquettes, brass-railed bar, white tablecloths on veiny marble. The lighting is forgiving; the Negronis are not. Chef Oscar Aviles Santana keeps things unapologetically classic: pasta alla vodka, veal meatballs, a Caesar salad heavy on the parmesan, cacio e pepe twirled from the wheel. Jazz eases you in; by midnight, it's old-school hip-hop. The original Cherry was opened in Saint-Tropez, but this one feels purpose-built for dinners that refuse to end.

“This is a restaurant we recently designed on a CHARMING, triangle-shaped corner in Saint-Germain-des-Prés- one of my favorite neighborhoods in Paris. It hits the perfect note: you can enjoy a great dinner with friends that easily extends into a late night, or just stop in for a solo drink at the bar. It’s also our first project in Paris so it holds a special place for me and the studio.”

“The spa is digital-free which feels like such a LUXURY these days. I don’t take a ton of time off so having this separation is so restorative, (and eye opening!). It’s set on a biodynamic farm that supplies much of the hotel's food and all of its florals, and the rooms within the spa have beautiful framed views of the surrounding grounds so you always feel a connection to nature.”

IN THE ENGLISH COUNTRYSIDE, A SPA DEVOTED TO SLOWING DOWN

A Georgian manor on 400 acres of Hampshire woodland, Heckfield Place opened in 2018 after a nine-year restoration—nothing here has ever been rushed. The Bothy came later, in 2023: a wellness space reached through the walled garden. Wildsmith takes its name from the estate's former head gardener, who spent his tenure curating the arboretum; the approach here is similarly considered. Treatments follow circadian rhythms, oils and soundtrack shifting with the time of day. Therapists work in naturopathy, osteopathy, reiki, kinesiology; the signature Wildsmith Time runs over two hours. Beyond the treatment rooms, there's cold immersion in the estate's lake, forest bathing among ancient oaks, reformer, breathwork, outdoor hydrotherapy with the farm's Guernsey cows grazing in the distance. The kind of place worth clearing a week for.

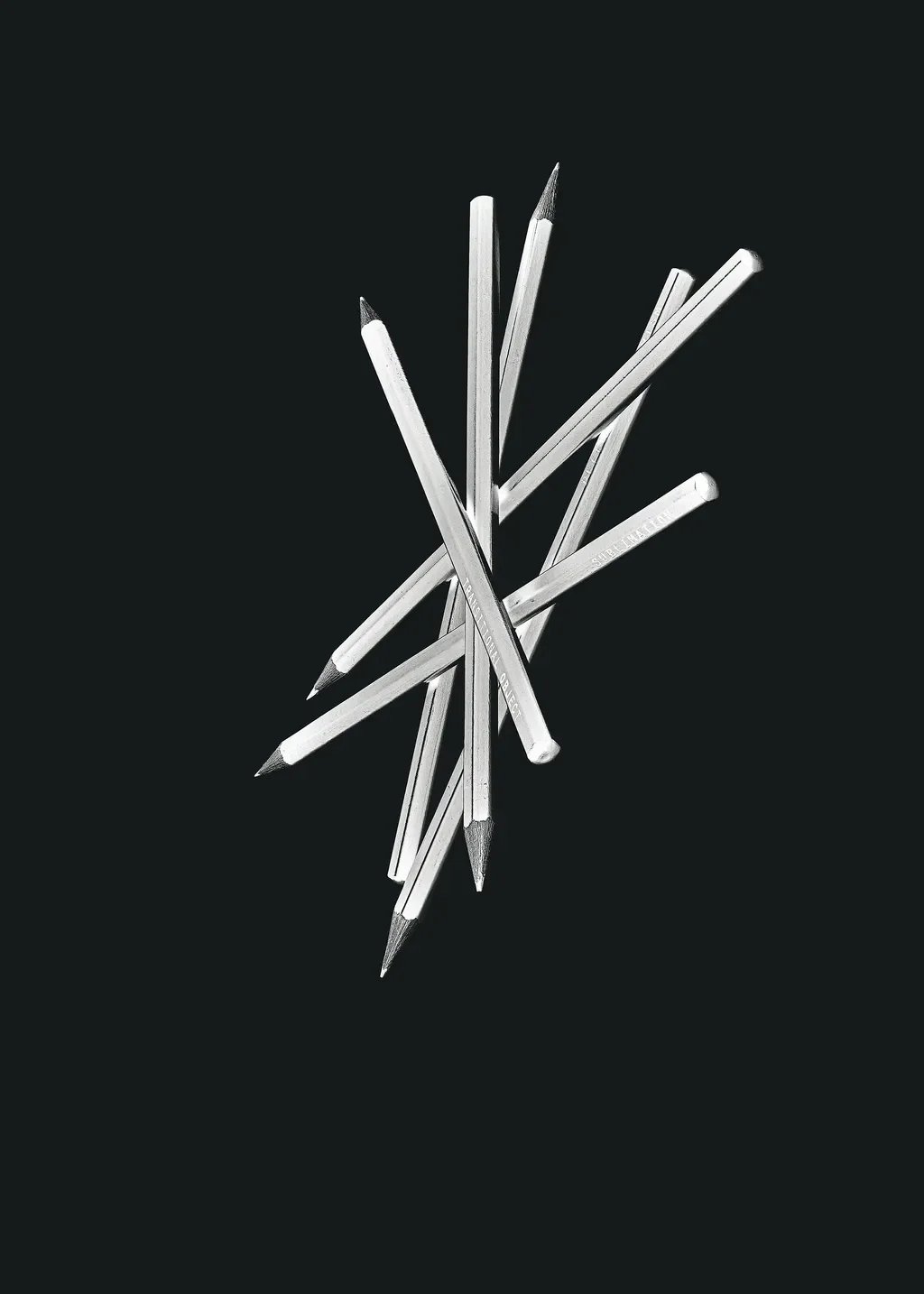

DESIGNED IN 1835, AND STILL SHARP

Staedtler has been making pencils since 1835. It's a skill they have quietly perfected. The Mars Lumograph is the one Norman Foster and Tracey Emin reach for, for reasons we assume are technical: 24 degrees from soft 12B to hard 10H, finely graded graphite that moves from velvety black to whisper-light grey without fuss, break-resistant lead that survives sharpening and the pressure of a deadline. The wood comes from sustainably managed forests; the metallic lustre photographs beautifully, if that matters. Nothing revolutionary—just a pencil that does exactly what a pencil should, every time.