On Girlhood

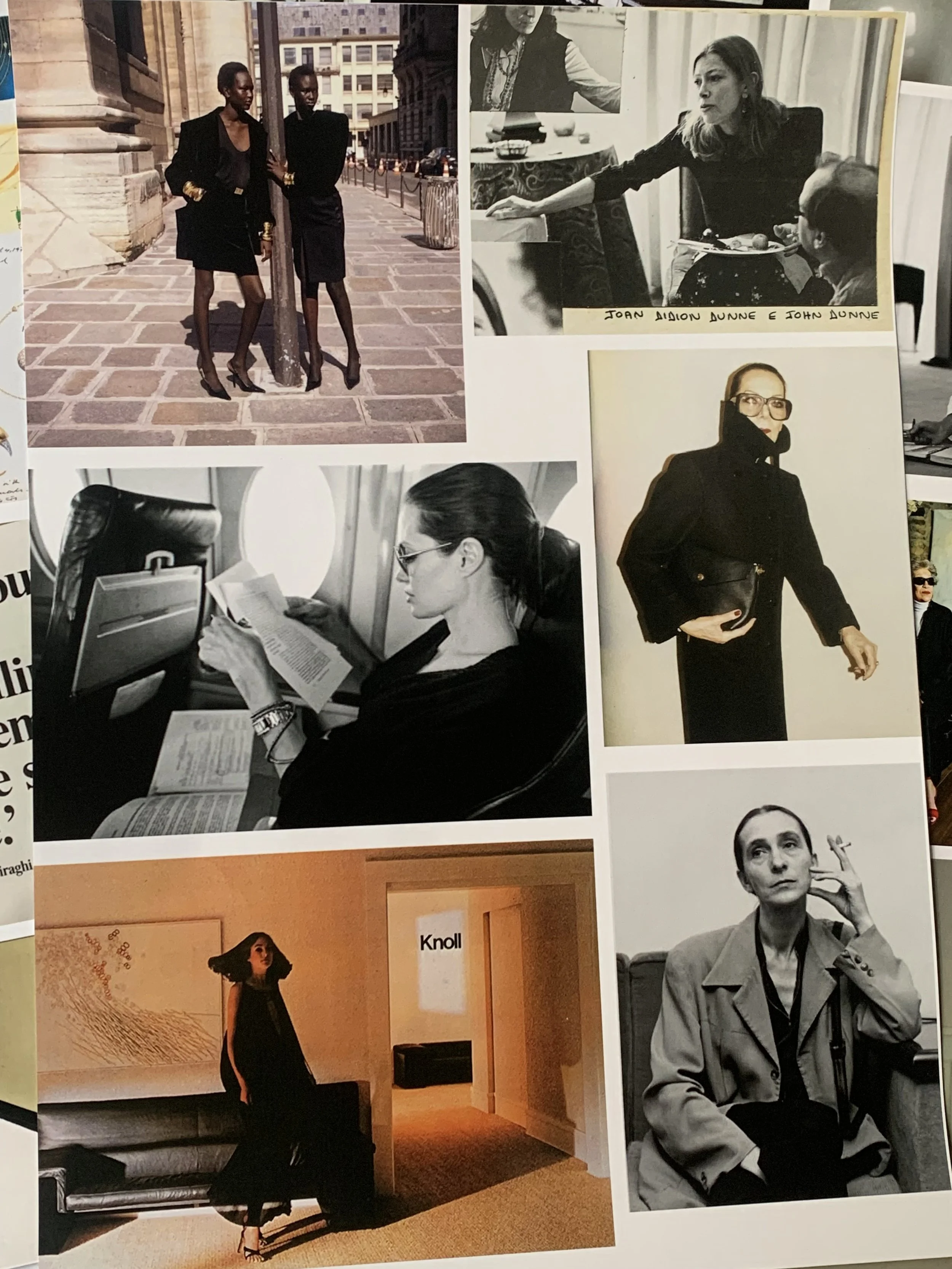

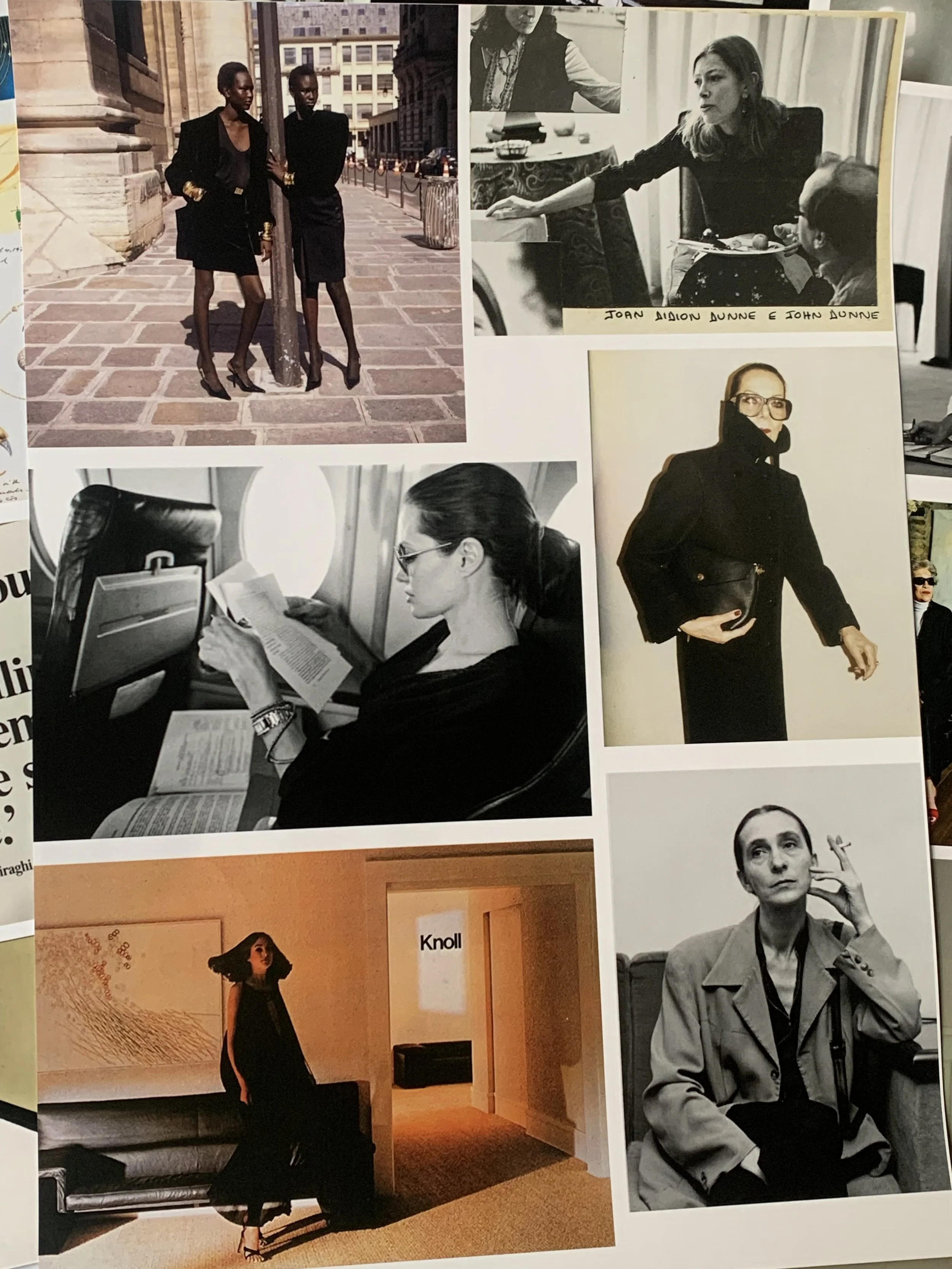

Collage by HURS.

On Girlhood

By Bonnie Langedijk

I have developed, over the past few years, an allergy. Not to pollen or shellfish or the particular dander but to a word. The word is girlhood, and every time I encounter it, which is constantly, something in me flinches.

Let me be clear about what I am not saying. I am not saying that girls do not exist, or that being a girl is not a profound and specific experience worth examining. I was a girl once and I remember it with the mixture of fondness and horror that seems appropriate to any honest recollection of adolescence. What I am questioning is the peculiar cultural moment in which grown women—women with mortgages and careers and the right to vote—have decided to retreat into the terminology of childhood as though it were a kind of spiritual homeland. As though womanhood were a disappointing destination we might, with enough pink merchandise and self-deprecating humor, avoid reaching altogether.

The word itself is not new. It emerged sometime in the mid-eighteenth century, around the 1740s, combining "girl" with that sturdy suffix "-hood" to describe the state or period of being a girl. Like childhood or adulthood, it was meant to mark a stage something you moved through on your way to somewhere else. The concept evolved, of course, as concepts do—shifting from the labor and domestic drudgery of pre-industrial girlhood to something more leisurely and psychologically complex in the modern era. Céline Sciamma made an extraordinary film called Girlhood in 2014, examining Black adolescence in the Parisian banlieues with the seriousness the subject deserves. The Preatures released an album by the same name in 2017. Dylan Mulvaney had a single called "Days of Girlhood" in 2024. The word dipped out of fashion in the 1980s—perhaps we were too busy wearing shoulder pads and pretending we could have it all to dwell on what we'd been—but it has surged back with a vengeance since 2000, and now it is everywhere, inescapable, hashtagged into infinity.

And I find myself asking: where is womanhood? What happened to the idea that the whole purpose of having a girlhood was to eventually leave it, to grow into something larger, more fully realized?

Here is the thing nobody seems willing to say: the pleasures we associate with girlhood do not actually require girlhood. The playfulness, the intensity of female friendship, the obsessive love of a musician or a book or a film that becomes, briefly, the organizing principle of your entire existence—these things do not diminish with age. If anything, they deepen. I am far better at friendship now than I was at fifteen. I know myself better, which means I know what I need from others better, which means I can actually be a friend rather than simply performing the rituals of friendship while secretly drowning in my own unexamined needs. The forty-year-old woman who discovers a new novelist and reads everything she's ever written in a fever of identification and excitement is not experiencing some embarrassing regression; she is experiencing the pleasure of a cultivated mind meeting material that feeds it.

But girlhood, as a brand, as a movement, keeps us small. It keeps us in a loop of purchasing. We are not buying things to celebrate who we have become; we are buying things to forestall who we are becoming. The creams, the serums, the aesthetics, the endless renovation of the self into something smoother, pinker, less marked by time. Women are already under extraordinary pressure to remain youthful—we did not need to build an entire ideology around it.

Don't misunderstand me. I own pink things. I have opinions about mascara. I can discourse at length on the films of my adolescence with an enthusiasm that might, to an outside observer, seem excessive. But why must these pleasures be cordoned off into girlhood? Why can't they simply be part of womanhood—part of the vast experience of being a woman, which includes frivolity and depth, lipstick and legislation, the ability to lose one's mind over a pop song and the ability to manage a budget? Why have we decided that women are either girls or mothers, with nothing in between and nothing beyond?

The girlhood movement, such as it is, has a certain uniformity that troubles me. A singular idea of what women—sorry, girls—are supposed to be. And usually this idea is pink and somewhat intellectually lightweight, more interested in shopping than in financial stability, more invested in the aesthetics of solitude than in actual nourishment. I have witnessed the romanticization of the solo dinner that turns out to be three crackers and some cheese arranged artfully on a cutting board. Three crackers with cheese is not dinner. It is a light snack. It is what you eat while you're waiting for dinner to be ready. The relentless performance of this kind of deprivation as self-care makes me want to lie down in a dark room.

So many products, so many brands, so many cultural offerings aimed at women seem actually to be aimed at teenage girls. And while I am all for catering to the younger generation—they are the future, they have money, they will inherit the earth or what's left of it—companies seem to forget that we do, eventually, grow up. Growing up does not mean abandoning the things you loved at fifteen; it means loving them differently, in context, alongside other things you have since discovered. It means having a relationship with your younger self that is tender but not identical. I do not want to be fifteen again. I want to remember fifteen, learn from fifteen, occasionally revisit the music of fifteen with a nostalgic fondness—but I do not want to live there.

And here is where it becomes more serious than aesthetics, more urgent than cultural criticism. We are living in a time when much of the progress made in women's rights sits on a precipice. The freedoms that seemed settled are being unsettled. The pendulum, as they say, is swinging back toward traditionalism, and there are forces—many men, and some women too, embarrassingly—who would like to see us return to more limited roles. Housewife. Mother. Nothing else. And I want to be very clear: there is nothing wrong with being a housewife, nothing wrong with being a mother. These are profound vocations, full-time occupations, worthy of respect and recognition. But choice is the essential word. The ability to choose these roles, rather than having them imposed, is what we have spent generations fighting for. And it seems to me that where society is heading is toward limiting that choice, perhaps eliminating it altogether.

In such a moment, hiding in the innocence of childhood is not an inexplicable response. I understand the urge to retreat. The world is frightening, and the news is relentless, and there is something appealing about the idea of being a girl again—unburdened, unaccountable, protected. I know I long to hide sometimes. But today, more than ever, we need women to stand up for the girls. We cannot protect the next generation by pretending to be part of it. We cannot fight for reproductive rights and equal pay and political representation while simultaneously branding ourselves as too cute and silly to be taken seriously.

“We cannot protect the next generation by pretending to be part of it. We cannot FIGHT for reproductive rights and equal pay and political representation while simultaneously branding ourselves as too cute and silly to be taken seriously.”

Girl dinner. Girl math. Girlhood. I know many people use these terms as comical references, as ironic self-deprecation, as a kind of in-joke among women who are perfectly aware of their own competence. But is this something to joke about? Are we in the position to be making ourselves the punchline? There is a version of self-deprecating humor that functions as a pre-emptive strike—you mock yourself before anyone else can, and thus you maintain control of the narrative. But there is another version that simply does the work of your detractors for you, that makes you smaller so that others don't have to bother.

What I am asking, I guess, is whether we might find connection as women rather than as girls. Whether that wouldn't, in fact, add depth and longevity to our bonds. There is research—there is always research—suggesting that women live longer partly because of the strength of their friendships, friendships that grow and deepen over decades, that move from the intensity of girlhood into something more sustaining. Girlhood is the root, but womanhood is the tree.

I do not have a tidy conclusion. I do not think the women who embrace girlhood are foolish or complicit or unaware of the contradictions. I think they are exhausted, and looking for relief, and finding it in a place that feels safe. I understand that. I just wonder if the safety is real. I wonder if what feels like play is actually a kind of cage—gilded, pink, aesthetically pleasing—but a cage nonetheless. And I wonder what would happen if we simply refused it. If we insisted on being women, with all the complexity and authority and hard-won knowledge that the word implies. If we stopped apologizing for having grown up and started celebrating it.