Gloria Steinem

Gloria Steinem, journalist, women’s rights activist, New York City, 2015. © Annie Leibovitz (pages 16-17)

Gloria Steinem

Women, Twenty-Five Years Later: Beyond Categories

Excerpted from Annie Leibovitz: Women by Annie Leibovitz with essay by Gloria Steinem © 2025. Reproduced by permission of Phaidon, Annie Leibovitz, and Gloria Steinem. All rights reserved.

By Gloria Steinem

I have not grown up in a world in which women are viewed as powerful as men, or in which the amount of melanin in our skin does not have some impact on social and economic status. Yes, there has been an increase in democracy, hard-won by many and of value to us all. And we are making progress toward valuing each human being as a unique miracle, even though we still categorize human beings in ways that often have no relevance in real life.

I came of age in the 1950s when the country was trying to get back to so-called normalcy after World War II. This often meant getting women and people of color out of the well-paying jobs that men had left for the military, and back into subordinate jobs. Women had little opportunity to use their talent, and men, too, were deprived of the full range of human emotion, from loving children to questioning the tyranny of being “man of the house.”

Most of my generation accepted the idea that the private/public roles of women and men were “natural.” Women were told to have children to make up for the losses of the war—a so-called national duty. If a woman had been able to have a job outside the home during the war, she was expected to leave it so the men returning from war could become heads of their households again. No one instruction is ever right for everyone, but especially then, it seemed unpatriotic not to obey.

Because I didn’t choose a conventional path and went off to live in newly independent India for two years, I was able to see more clearly how much women were limiting themselves. I wanted desperately to go to India, but I also wanted to break an engagement to a charming man, and knew going halfway around the world would be a way out. After too many days in the TWA office pleading for a free airline ticket, I got as far as London, where I had to wait for my visa to India. While there, I found out I was pregnant. Abortion wasn’t legal, but if I could find two doctors willing to give me permission, I could obtain one. The first brave doctor made me promise him two things in exchange. One, I would never reveal his name, which I did not until I was sure he was no longer with us. Two, I would do what I wanted to do with my life. I have tried.

As a 1950s person, it was considered an odd adventure that I was living in a no-children, unmarried way, the opposite of what I had been told to do. By the time I came home from two years in India, the rebellious sixties were beginning, and my less conventional path was becoming more familiar.

The sixties gave us all—women and men—more freedom. Women began to ask, “How can I combine career and family?” Some began to realize that they had set their sights way too low. Though women were breaking out of more limited roles, most weren’t yet trying to change the world to fit women; we were still trying to change women to fit the world.

So much activism was beginning, whether against this country’s misconduct of a war in distant Vietnam or its domestic and tragic segregation of races. Big segments of our population were beginning to protest these crucial negative actions. For those of us who were female journalists, or always assigned to domestic and other non-controversial subjects, we knew that we had to become editors and publishers ourselves if we wanted attention on our own universal interests and values.

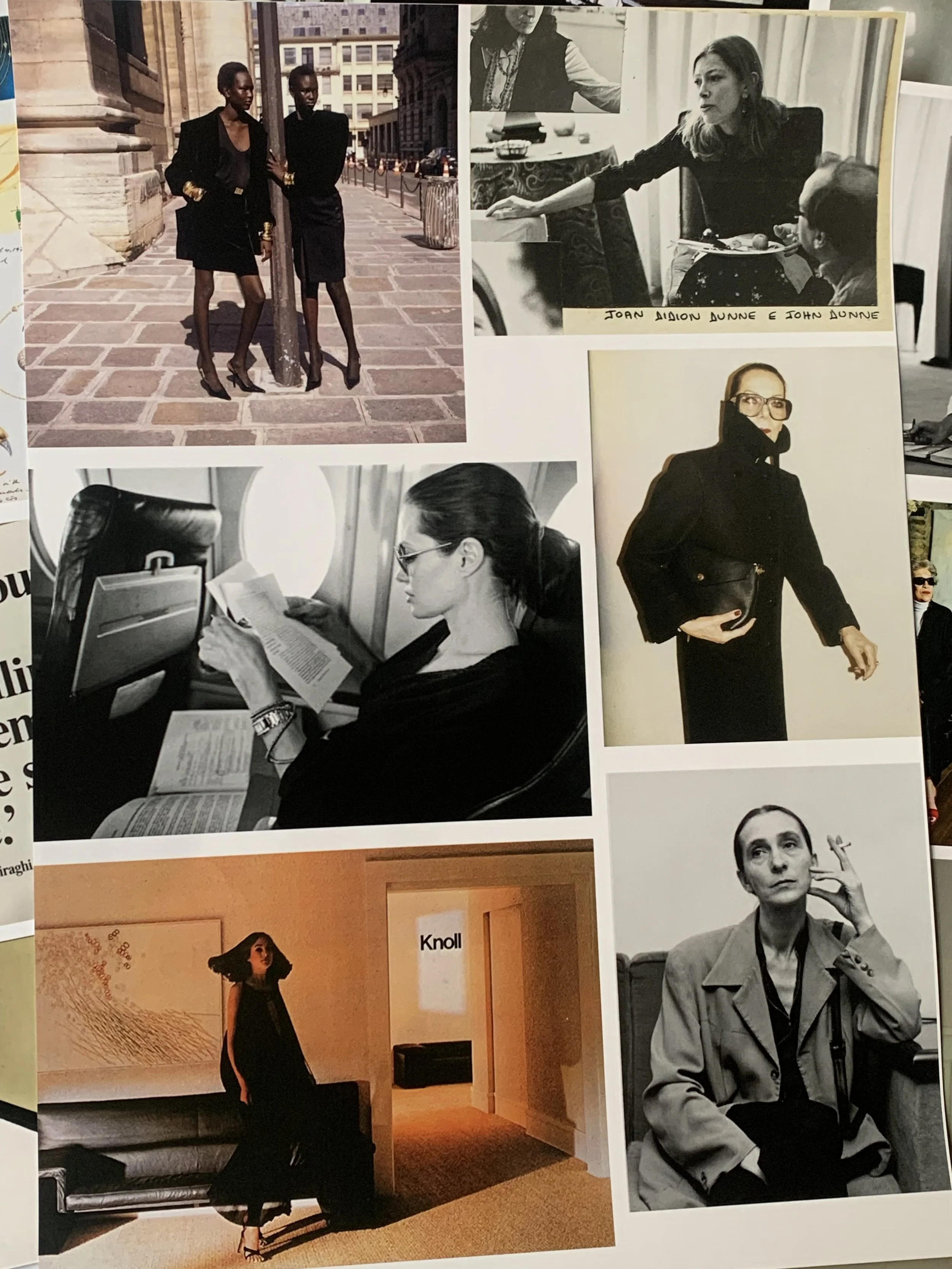

With this in mind, a small group of women writers and editors began Ms. magazine, the first national magazine to be created, owned, and controlled by women. This included seeking out ads that featured a woman at a desk or driving a car, not just in the kitchen or holding a child. Since very few such ads existed, this also required visiting advertising agencies and asking that they add these realistic images, a task rarely successful because such images weren’t perceived as “aspirational.” This made us realize that to be consistent, we ourselves should assign and employ women where they had rarely been before, including women photographers to shoot covers. We soon discovered that women could be reportage photographers recording street scenes, but not frequently portrait photographers, who required lights and a studio, necessities that were beyond their earning power.

When we were looking for female photographers, we discovered Annie Leibovitz, the very rare photographer who was, even then, unlimited by space or subject. In 1970, she joined Rolling Stone, a national monthly magazine that focused on music, politics and popular culture, creating photographs that were true to each subject, yet also recognizable as hers.

Looking at Annie’s book, Women, from twenty-five years ago, I see women represented in all of their diversities. Many project strength in those images, but it didn’t mean that came to them naturally. Her subjects didn’t always have easy or comfortable lives, but they did share a common theme of using even their weakest moments to turn their lives around. Those brave, bold women were still exceptions in our society and Annie’s attention legitimized them. This was especially true of women trying to inhabit industries that had been defined by masculinity: for instance, sports and politics. For myself, I spent too many years being the “only” girl reporter. My male colleagues were always supportive, but they also treated me like an exception.

The images show women negotiating with a world that didn’t quite value femaleness. As Susan Sontag said in her important introduction to Annie’s book, “A man can always be seen. Women are looked at.” Like the teenage heroine in Gypsy who is aware of her body only after she becomes a stripper, too many of us experience female bodies, our own and others, only when they are on display. Annie’s vision twenty-five years ago rendered visible the triumphs of women who had been invisibilized or excluded by the public view. This is best personified in the showgirls represented in this volume. They are one-hundred percent authentic. How wise of Annie to show us their true selves.

Over a decade after the first Women book was published, Annie had a touring exhibit, “Women: New Portraits,” which went to many cities around the world. In each locale, Annie and her team managed to find some symbolic place to house the exhibit. In New York City, there was a big room at the Bay View Correctional Facility, an old building whose walls had once restricted rebellious women prisoners.

I was lucky enough to tag along to some locations. Annie’s gift for capturing her subjects was known to the world, so at each stop there was an outpouring of support. Annie captured women ranging from CEOs to star athletes and environmental warriors, displaying them in rooms with physical canvases and large digital screens. The result created a great conversation among women as they toured these rooms together. Each of us who visited felt represented by both the images and the audience.

Before long, these exhibits became meeting places. I introduced Annie to “Talking Circles,” which I learned about from Indigenous communities in North America. The idea is that everyone in the circle has the opportunity to speak and also be heard. Women spoke about themselves and discussed issues. It was inspiring to see people connecting across generations and professions and even continents, yet it gave me pause to hear so many women still struggling with what it meant to be a woman.

As a traveling observer, I was able to join these magical groups attracted by the appeal of Annie’s human and universal images. Some women came from wealthy families and were being denied access to their family wealth or businesses. Others were sheltering women fleeing from unsafe homes and trying to create systemic change of domestic violence, not just temporary housing. Many were trying to become role models for their daughters or to encourage their daughters to pursue the right to an education and work of their own.

The women portrayed in this new edition of Women are a proud reflection of that feminist rebellion, self-respect, visibility and humanity. I’m happy to see that women now are likely to value our own minds and hearts, and to have faith in the importance of our own making. Most of these women have succeeded beyond their own imaginations and are filling out a historical documentation that hasn’t been equal. Many of these women are succeeding at the highest levels, and in doing so, have made it possible for every woman to raise our expectations.

While these photos focus on unique individuals, each image invokes multiple questions about its subject. The goal isn’t solely to appreciate an image, but to respond to the emotion it excites. We expand our consciousness by taking in the reality of others.

In this book, you will see images that can be appreciated individually. Taken together, they narrate progress women have made over the generations. This book couldn’t have been compiled twenty-five years ago. We needed more decades for women to evolve more into their full human potential.

In fact, this book is not only a view of women, but a testament to what has been and what is still to come. It’s a reward of realities to see the world without the assumption of anything except unique and globally universal human beings. For too many decades women were encouraged to measure ourselves against a myth. We sometimes foolishly accepted some of this. Women have been said to have smaller brains, passive childlike natures, to be unable to govern ourselves, and to have limited job skills. We were also told that we were good at detailed work, as long as it was poorly paid. When it was brain surgery, we were suddenly not so good at it. This made women into overeducated and poorly paid office workers, and men into medical, academic, and political authorities.

“How we are seen no doubt CHANGES how we see ourselves. The photographs in these books represent how women have evolved from object to subject over the decades.”

How we are seen no doubt changes how we see ourselves. The photographs in these books represent how women have evolved from object to subject over the decades. Today, women have transcended many barriers of self-actualization and have the rewarding and challenging job of becoming our unique selves. But there is a deeper and harder question before us: how are we as women limiting ourselves? It’s much easier to point out what’s wrong than to build a just world. But building a more inclusive and respectful world is exactly what we need.

I know many people now feel our country is going backwards, but when you have lived a long life, which I am lucky to have done, you have a context of: compared to what? We survived McCarthy, we survived Nixon, we can survive what feels like regression. A perspective that maybe only my age peers and I can have, but being condescended to is progress. Previously, we were just ignored. I remember times when thoughtful male journalists would look at a roomful of women and report, “there’s no one here.”

Another example. Even the otherwise well-meaning New York Times took until 1986 to use the term Ms. Men had been referred to as Mr., but any reference to women (Miss or Mrs.) was entirely dependent upon their marital status. I was well into my fifties and the newspaper was still reporting on me as Miss Steinem of Ms. magazine. When the publication finally caught up with progress, we sent a big thank you to Abe Rosenthal, who was then the executive editor of the Times. He thanked me and said, “If I’d known it meant so much to you, I would have done it sooner.” This after years of writing to and demonstrating against the Times!

Annie’s images demanded that women be seen. I think these photographs are a most valuable time capsule of that evolution. Saving writing is important, but it is limited by language. Saving images is preserving the most universal and nonverbal form of human communication. It is a gift of our shared humanity. Women isn’t just a collection of women, it’s a history of our time, with women included. It’s a documentation of the people it captures, and the environments they thrive in—from cluttered kitchens to seascapes, women inhabiting space with authority and grace.

This book will help us to discover our adventurous true selves. I know that some writers and scholars describe this as putting on a feminist lens, but that sounds too much like filtering reality. It’s more accurate to say we are taking off a patriarchal lens. Perhaps feminism is to society what the new physics is to the old mechanical model: both challenge the assumption that any one person or group can be central. We are atoms whirling in place, affected by and affecting those near and far from where we are.

The idea that all people are equal shouldn’t be radical. It may have seemed so once, but not for the next generation of women who are overcoming the idea of categories of human beings. The book itself defies categorization because women ourselves can’t be so neatly categorized. The more we live with equality, the more we know how greatly all our lives are improved by it. Limiting human potential is a limit on all of us. The lasting gift of this book is that it can free our imaginations.

Gloria Steinem, New York City, 2025