Can Art Be the Key to Integration for Refugee Women?

Photography by Irma Labelle

Can Art Be the Key to Integration for Refugee Women?

By Anna Prudhomme

Today, the path to integration for refugee and asylum-seeking women remains steep. Despite high levels of education, many migrant women find themselves sidelined, confronted by language barriers, systemic discrimination, social isolation, and the trauma of exile.

According to the European Institute for Gender Equality, on average, the employment rate for refugee women in the European Union is 45%, compared to 62% for refugee men. They are more likely to be unemployed or economically inactive than any other group in the EU labor market.

For these women, mastering the language of their host country is a gateway to employment, autonomy, and participation in society. Yet traditional language instruction often overlooks the specific challenges they face, both as migrants and as women.

That’s where the École Monique Apple comes in. Founded in Paris in 2021 by Elisabeth Bettencourt, the school offers a radical alternative: a feminist, person-centered approach to French language education, focused on professional integration, collective empowerment, and societal immersion. Named in tribute to Bettencourt’s mother—an artist and writer who embodied values of care and justice—EMA is as much an educational project as it is an integration one.

The school has partnered with the Jeu de Paume, one of Paris’s leading contemporary art institutions, to develop a unique module titled “Integration Through Art.” The program invites newly arrived women to learn French in direct dialogue with visual culture. Through exhibition visits, writing workshops, and public speaking sessions, participants not only improve their language skills, they build confidence, foster community, and find space for their voices in the cultural landscape of their host country.

How can art serve as a powerful bridge between language and belonging? In this piece, we explore how the team at École Monique Apple offers women not only tools for communication, but also pathways to independence and social inclusion.

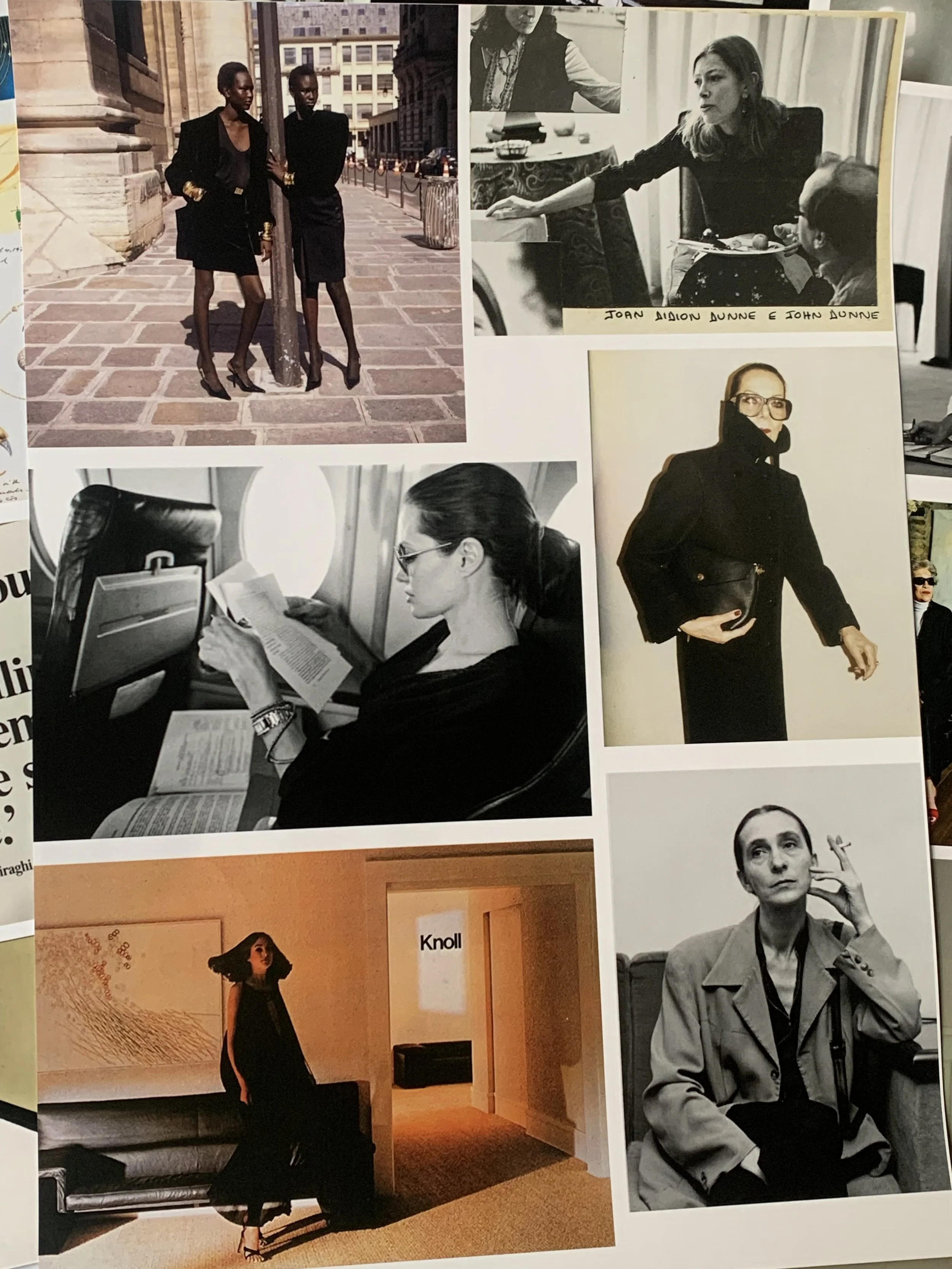

Photography by Irma Labelle

Photography by Irma Labelle

École Monique Apple: A Pedagogy Rooted in Language and Human recognition

“We created EMA because the needs of migrant women holding qualifications from their country of origin were not being met by existing programs,” says Elisabeth Bettencourt, founder and director. EMA is “the only professional French-language training program in France that functions as a true safe space.” “Too often, language education is disconnected from the realities of migration—of trauma, of professional experiences lost, of lives interrupted,” she explains.

EMA’s pedagogy breaks with this disconnection. Inspired by feminist, holistic, and action-oriented approaches, the school treats language not as an abstract system but as a living tool. Learning happens through: visiting museums, navigating bureaucratic systems, expressing emotion, preparing CVs, and identifying and valorizing participants’ skills and experiences. But mostly, EMA is a diploma-granting school that prepares women to take the official French exam, required to obtain a legal residence permit and access professional training.

The school works with each woman’s lived reality, acknowledging the emotional weight of displacement while creating room for new narratives to emerge.

The environment is key. Class sizes are small, and the teaching team is deliberately multidisciplinary, bringing together FLE (French as a Foreign Language) teachers, theater practitioners, artists, voice coaches, and cultural mediators. Courses are offered free of charge and tailored to different proficiency levels, always with an eye toward employability and self-recovery.

Central to EMA’s ethos is recognition. As Bettencourt explains, “Many of the women we work with have been doctors, artists, administrators, teachers. We don’t teach them as if they know nothing. We begin with what they already know.” The classroom becomes a space of mutual respect, where participants can shed the label of “victim” and instead step into roles of speaker, learner, guide, and even teacher.

The school’s feminist orientation is not just symbolic; it shapes how classes are taught. Power dynamics are flattened. Dialogue is privileged over correction. Emphasis is placed on collectivity and listening. Valerie Bretaud, the school coordinator stresses “the importance of feminist pedagogy, which also takes shape through gestures, attitudes, and the teacher’s discourse with the group. An instructor’s behavior directly influences how a learner relates to language acquisition. The women here evolve in a setting where their voices are solicited, legitimized, and valued, a setting where transmission is horizontal and differences are visible.” She cites Perry Beaumont’s definition of emancipation: “identifying one’s own linguistic and cultural limits in order to bypass them, break them, let them fall, and transcend them.” For Bretaud, art is a remarkable tool to do just that.

The methods rely heavily on peer learning: the women advance together, benefiting from the momentum of a group facing the same difficulties. Art facilitates the intercultural dimension; it becomes a motor, a link between women who are discovering together.

Language Through Images: Inside the EMA and Jeu de Paume Art partnership

In a light-filled exhibition room at Paris’s Jeu de Paume, a small group of women stands before a black-and-white photograph. Since its inception, the “Integration Through Art” module has operated on a simple but radical premise: engagement with visual culture offers the freedom to think and feel, even when words are still lacking.

Each cycle is built around three encounters: an introduction led by a museum educator, a curated exhibition visit at the Jeu de Paume, and a final session in which participants publicly mediate selected artworks.

In 2024, exhibitions by 20th-century Italian photographer Tina Modotti, French contemporary artist Bertille Bak, and American photographer Tina Barney served as creative catalysts. A highlight came on January 17, 2025, when EMA’s most advanced learners presented their reflections in the gallery spaces, speaking in pairs before a public of their peers.

“Many of the WOMEN we work with have been doctors, artists, administrators, teachers. We don’t teach them as if they know nothing. We begin with what they already know.”

“As many language acquisition theorists argue, the classroom cannot be the only place of learning,” explains Bettencourt. “So we move away from the classroom toward the city.”

At the heart of the program is a belief in art as a soft technology of integration. In a 2020 report published in the French journal Hommes & Migrations (Men & Migrations), Bettencourt noted that “artistic practice allows migrants to build new narratives of self” and “access symbolic and emotional registers that conventional integration tools often ignore.”

EMA’s pedagogical model reflects this insight. Working in small groups twelve, with tailored language support, participants are encouraged to produce their own interpretations. But the women also gain a sense of cultural belonging. Bettencourt emphasizes, “We are not teaching them about France. We’re opening a space for dialogue, between their stories and the stories told through art.”

Their main goal is to give back a voice to those who lost it on the path of exile. By encouraging interaction with artworks, women can, even with few words, express singular thoughts enriched by their cultural and personal experiences. Some participants even possess more artistic knowledge than the teaching team. The cultural mediators identify and highlight these insights, connections, and lived references during discussions. On their side, the mediators focus on educating the gaze; they don’t overload with information. What is valued is the act of looking.

Finding Voice Through Art : EMA Participants Speak

Among EMA’s participants is Natalya, who arrived in France in 2022 after “an unplanned departure” from Russia, where she had been working in human rights and higher education. The first months in Paris were marked by administrative hurdles and the shock of navigating daily life without French. She was “honestly surprised that nobody wanted to speak English,” a stark contrast to her past travels in Europe. Over time, and with the program’s support, her anxiety about speaking lessened, though she admits with a smile that “answering the phone when it’s the delivery person is still a five-star challenge.”

For Natalya, the art-based learning approach was transformative. “The language of art can be understood no matter what language you speak. You perceive with the heart, and you learn to understand French on an emotional level. It’s an amazing experience.” She recalls how museum staff made a special effort to simplify their speech, and how preparing her own presentation on an installation taught her “how hard it is to talk simply about complex things.” What she values about EMA is also the safe, women-only environment: “you can be vulnerable without feeling exposed, and that creates real sisterhood.”

Another participant, R., originally from Bangladesh and a former math teacher, also stood out. Throughout the process she remained highly motivated. On the day of the public restitution, she took the floor confidently, explaining an artwork by linking it to her knowledge of binary language. In that moment, the roles reversed, and the notion of “transmission” took on its full meaning.

Valeria, an architect and engineer from Ukraine, arrived in France at 35 with her young son, forced to leave everything behind when the war began. The language barrier was her greatest challenge: “Not speaking French made me completely dependent. It left me feeling useless, like a teenager instead of an adult.” Just one month after arriving, she joined EMA. In only six weeks she reached level A2, but more importantly, she rediscovered confidence. “It’s not only about learning French, but using it — that’s the real strength of EMA. The workshops, especially with actresses, felt like therapy. I overcame fears that were blocking me.”

At first, however, she admits she was skeptical: “Coming from a post-Soviet educational system, I was used to a very theoretical approach, memorization, and strict control. Creative workshops and excursions seemed almost like a waste of time.” Over time, those very experiences became turning points. “These visits were a crucial step in my integration. As an immigrant, you are not a tourist, you rarely have the time or opportunity to discover Paris or visit museums. Having it as part of the program pushed us to explore. It was also enriching to see the reactions of other students, to hear their impressions, all coming from different cultures. This multiculturality is also part of French culture, and the collective outings gave us the chance to experience it fully.” Within a year, Valeria had advanced to B2, completed professional training, and secured a position at a leading engineering firm in France’s ecological transition sector.

Photography by Irma Labelle

Photography by Irma Labelle

Beyond museum visits, participants have also taken part in workshops led by Fine Arts professors, such as “Drawing, Writing, Gestures” with artist Mathilde Salve, and art mediation sessions with art historian Francis Moulinat, including visits to the iconic museums Petit Palais and the Musée Carnavalet. These activities expand the women’s exposure to France’s cultural heritage while giving them new tools for self-expression—combining language acquisition with creativity, observation, and dialogue in professional artistic settings.

As Bettencourt explains, “These courses followed three steps: description, impressions, connections. During visits, we would only look at two or three paintings at most. The professor led a discussion in front of the works, and the quality of the women’s critiques, despite their limited French, was astonishing. It gave all of us a profound sense of pride.”

In collaboration with language instructors, EMA also designed two pedagogical projects directly based on artistic processes, encouraging freer, more experimental, less linear learning: one with a photographer (Words, Images and Identity), where women work on portraits and self-portraits; and another with a filmmaker, where they produce a poetic mini-documentary. The first film, Paris Vu par des femmes venues d’ailleurs (Paris Seen by Women from Elsewhere), was created with complete beginners.

Art as a Catalyst for Integration

For Elisabeth Bettencourt, art is not an add-on but a catalyst: “Art teaches difference, tolerance, and how to welcome the unknown. The creative process itself becomes a model when you have to rebuild your life.”

From the very start, participants embark on a professional path but what distinguishes EMA is the collective dimension: progress happens in the presence of others. “They move forward together, drawing strength from a group facing the same challenges. It’s deeply moving to see bonds form between women whose origins and cultures are so different.”

In class and at the museum, art becomes the common ground. Looking at an artwork together teaches participants to observe without fear of misunderstanding. Bettencourt notes: “In front of a contemporary piece, some like it, others don’t — and that’s important. One former student told me: integration succeeds when you feel you have the right to say no.”

Photography, video, and contemporary installations often provoke the liveliest exchanges. But even classical works can resonate in unexpected ways: French painter Édouard Manet’s On the Beach, “unlocked memories, sensory references, and intercultural conversations I could never have anticipated.” Women artists also spark strong identification, not just for their art but for their stories of resilience and creation. These encounters turn language learning into a process of empathy and discovery.

“With an artwork as a starting point, even beginners can express an opinion — you don’t have to wait for an intermediate level,” Bettencourt adds. Supported by cultural mediators, participants move beyond the binary “I like / I don’t like” and instead build nuanced views. The impact spills beyond the classroom: going to three or four exhibitions per cycle, navigating the city in small groups, finding the right address — all of it nurtures autonomy and confidence. Bettencourt recalls women who hardly spoke in class“finding their voice at the museum, because French was their only shared language.”

Challenges and Opportunities in Practice

EMA’s approach is designed for speed and depth: professional integration, collective empowerment, and immersion. Yet implementing such a vision brings challenges.“Many women arrive in emergency situations where everything feels urgent,” Bettencourt explains. At first, some dismiss the art module as less important than conjugation. “Those already curious about art join right away; others find excuses. But over time, almost all of them come and the progress of those who attend convinces the rest.”

There are systemic hurdles, too. While cultural institutions are increasingly eager to welcome audiences considered “far removed,” partnerships with adult migrant training centers remain rare.“Sometimes there’s a degree of condescension from museum professionals toward adult educators, who themselves may feel distant from art,” Bettencourt admits. “Our role is to model what’s possible and to help other centers develop similar programs. Art shouldn’t be reserved for an initiated few.”

Beyond the practical benefits, Bettencourt sees something fundamental: “Learning a language as an adult is an act of creation; integration is too. Developing creative capacity is essential and that is exactly what art is all about!”